Timeline

10 weeks

Team Size

5 Public Policy students, 1 HCI student

Summary

As part of the Design in Policy course at RIT, I was part of a team of policy designers tasked with developing policy solutions to improve the Rochester Regional Transit System (RTS) user experience for the local refugee population, using UX design methodologies.

Our client, Mary's Place, is a Rochester-based non-profit organisation that works towards the resettlement and welfare of the local refugee population. They came to us with a broad request to address the needs of refugees through effective policies and design solutions.

Based on 6 interviews with a diverse group of refugees and site visits to Mary's Place and Rochester's transit center, we identified the local transit system to be inaccesible to refugee users due to:

A complex bus system,

Lack of communication,

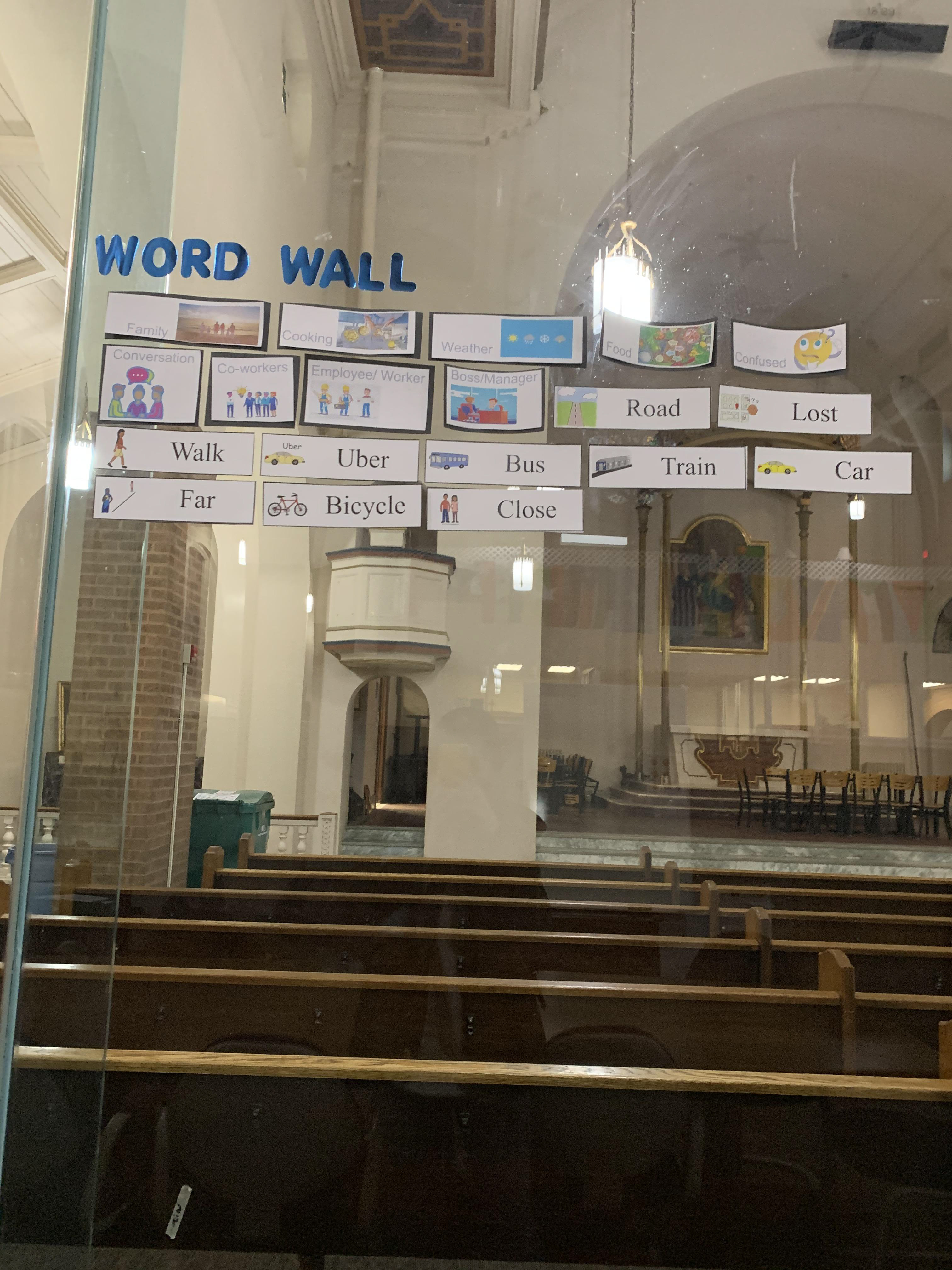

Lack of resources for English Second Language or non-English communicators,

Dependence on digital apps/websites for bus routes and updates,

Low self-confidence after bad experiences with the RTS in the past.

These findings were extremely disconcerting, as these problems directly affected thousands of Rochester residents, and overlapped with the problems faced by non-refugee populations who relied extensively on the RTS for their day-to-day commute.

We utilised the insights from the user interviews to identify key pain points in the transit experience, and developed both design-based and policy-based solutions. The final policy proposal was presented to Mary's Place, and was later presented to RTS's Board of Commisioners.

Process

Design Brief and Initial Brainstorming

We were approached by Mr. Matthew Palocy, Program Director at Mary's Place, with a brief about the local refugee population and potential issues we could address. Some takeaways from this presentation were:

Rochester hosts 1% of the total annual incoming refugee population in the US.

Refugees, in general, have a difficult time time adjusting to their new home, and may have trouble with communicating in and reading English.

Refugees frequently face financial difficulties, and rely on public transit to and from low-income housing areas.

Mr. Palocy highlighted the impact of low-income housing on the well-being of our users, and suggested that we look at developing solutions to improve their housing condition. Based on this suggestion, we developed some initial questions for user interviews, focusing on the condition of their housing, safety, and coping with the extreme weather conditions in the winter.

User Interviews at Mary's Place

To meet with our users, we visited Mary's Place on their weekly food and welfare distribution day. In preparation for these interviews we kept the following in mind:

Interviews would have to be conducted in multiple languages. Therefore, we needed to identify one or more interpreters in-situ, who would help us speak to ESL or non-English speaking interviewees. I was one of the researchers who could communicate in both English and Hindi, and took the lead on half the interviews. On the day of the interviews, we relied on Mr. Palocy's suggestions to identify individuals who could communicate in English sufficiently to answer our questions, and also asked second-generation refugees to act as interpreters.

Interview questions would have to be framed carefully, to avoid triggering PTSD in our interviewees. We carefully steered away from asking questions about their experience prior to arriving in the US, and focused on their present-day experiences instead. We asked Mr. Palocy to vet the questions in advance, to ensure that we made the interview experience safe for our users.

On the day of the interviews, we recruited 6 interviewees from multiple nationalities through random and snowball sampling. Frequently, we would interview two or more people simultaneously, with one person answering in consultation with the other/s. We found that this made them feel safer, and that we were able to get a lot more conversation flowing. Communicating effectively and sensitively while being unable to speak in the languages of our users was a bit challenging at first. It was extremely important that we respect the time given to us by our users, and to respect what they saw as urgently in need of improvement.

Even though our questions were quite structured, we left room for subjectivity by asking them to share what was challenging in their current experience. After our first two interviews, we quickly realised that the key issue appeared to be an inaccessible and inefficient public transit system. We regrouped and changed our questions to better understand why the RTS experience was unpleasant for our users, and quickly realised that this was a common issue across the board.

An important aspect of the interview process that we had somewhat overlooked was the effect that the stories of each individual would have on us, as researchers. I found that it was important to remain empathetic, without imposing my emotions on the interviewees. I was glad that we had prepared questions that would elicit fairly neutral responses, and would not subject interviewees to harm, but I think that even basic questions about accommodation and the transit experience can carry a lot of weight.

For example, one interviewee shared their experiences with feeling lost and confused on the transit system, and being unable to go back on the bus independently ever since. Another interviewee shared their worry about their mother getting lost while travelling home from the hospital, because she completely forgot her stop. These stories really showed us that public transit was something we could not afford to take for granted.

AEIOU Framework

We utilised the AEIOU framework, i.e., activities, environment, interactions, objects, and users, to categorize our data.

We identified key points in our users' experiences with using the RTS. We started to see that the dependence on the public transit system, and inefficiencies in the system, directly impacted our users' essential activities, such as going to school, work, or the hospital. This also meant that a poorly planned itinerary would severely affect users' access to food, clothing, and welfare services.

Despite the inefficiencies, the main reason for this dependence was the affordability of the RTS. Each trip costs $1 per person, regardless of the start and end points.

Cultural factors also seemed to play a big role in the issues our users faced. For example, sitting next to a stranger on the bus, especially a man, was uncomfortable for multiple women we interviewed.

Amongst our users, only one could afford to own a car, and were able to get one almost 10 years after having relocated to the US. They specified that they used public transit extensively when they lived in another state, for almost 8 years prior.

Affinity Diagramming

We utilised Affinity Diagrams to draw a better picture of specific reasons that influenced our users' experiences and choices.

Some key takeaways were as follows:

Most users relied on welfare checks due to a lack of employment opportunities.

Travelling by bus was a core part of everyday activities for most users, primarily due to its affordability.

Most users had some community members they regularly kept in touch with, but had trouble speaking to strangers, or people outside of their own ethnic communities.

Most users had difficulties communicating in English, and had almost no English reading proficiency.

Most users described the current RTS bus system to be complex, and difficult to comprehend.

Example of a confusing and difficult to understand RTS Map for a common route to the hospital

Personas

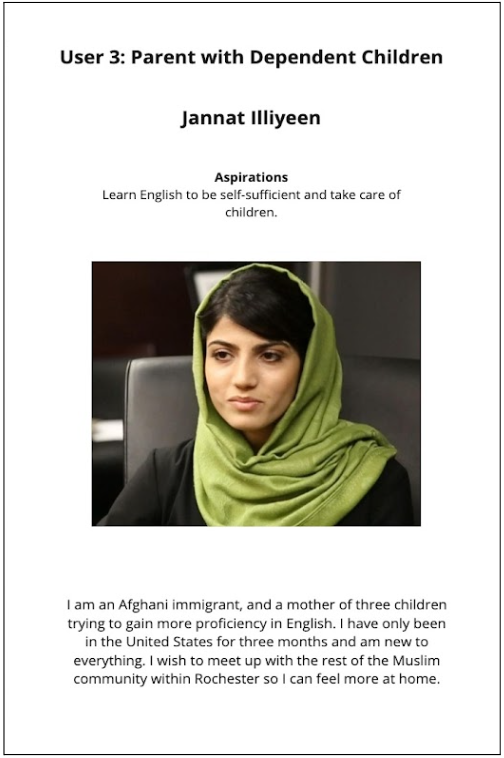

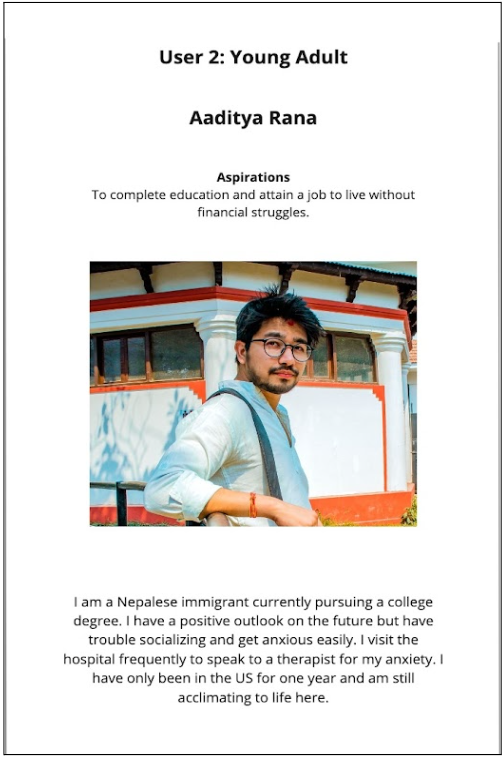

Based on the interviews and resulting insights, we developed 3 user personas. Please see them described below:

Behavioral Mapping

We outlined locations along the RTS network frequented by each persona and how they would navigate to those places from their home, to better contextualize their most common behavior with respect to the RTS.

First, we used Google Maps to pinpoint common places that refugees would need to navigate to from their home - Walmart, Mary’s Place, School, Hospital, etc. Then, we identified the most common bus routes taken by refugees currently - routes 10, 15, 150 - from their homes to these key places and back.

Behavior map for Lily, Jannat and Aaditya

Cognitive Mapping

Creating a cognitive map allowed us to visualise how our users were thinking through the Rochester bus system and find travel patterns based on interview data.

For example, a user travelling to the Center for Refugee Health may not have the option to get a continuous bus journey from their point of origin, and may be forced to transfer into a second bus, and will also be required to walk about 0.3 miles from the nearest bus stop to their destination. This journey might not be accessible to users who may get confused, anxious, or lost at the transit center, or for users with disabilities, with no additional support.

The cognitive map demonstrated the difficulty associated with refugees being able to travel independently and confidently between multiple locations, especially considering that they have to use public transportation or walk between locations. These issues are further compounded by the difficulty in communicating with RTS staff members in English and the lack of access to technological support like smartphones or GPS tools due to unfamiliarity, age, inhibitive costs, etc.

Design and Policy Solutions

I have decided to omit the design and policy solutions we prepared to meet the class requirements, given that we were unable to reconnect with the users we had initially spoken to. These solutions are untested by us in the context of Rochester’s refugee population’s needs, and including them here would not be in line with HCD principles.

The long distance between Mary’s Place, the residential locales of our users, and our institution posed a significant challenge. We were authorised to use institutional support to visit Mary’s Place only once, without risking missed classes (the RTS bus ride would take up most of our time) or expensive ride-sharing options. Most of us did not have access to a personal vehicle, either. It was crucial that we kept in mind that our proposed solutions were not going to be tested, and it was collectively decided that we would omit them while approaching any authorities without a direct investment in the welfare of our users.

We shared our findings as well as potential solutions with Mr. Palocy, so that another team could use and test their applicability and effectiveness. We shared a compilation of our user research as well as literature reviews of similar approaches to re-designing public transportation with the Rochester Regional Transit System (RTS) board, as part of a 2021 drive to update the routes and services offered by them.